The Glock 17: From Revolutionary To Routine

I want to do an experiment with all of you right now. Before you even go further let me ask you do one thing.

Think of a 9mm handgun.

And give me an answer fast. Don’t think, don’t dawdle, just say the first thing that shoots to your mind.

Right. Go.

You got it in your head? Good.

Was it a Glock?

Thought so.

It’s not a trick question mind you, to have this thought come up first and foremost. For an American, or even any person, the Glock and by proxy handguns like the Glock 17 and Glock 19 are now borderline default arms. It’s a kneejerk reaction to think of that, because of how overwhelmingly common the arms have become on the international and domestic markets. Civilian, military, police, with 73 different nations and hundreds of police agencies using a variant of the Glock system. Over 20 million Glock pistols have been manufactured, and that’s a citation from 2020. That same year, GunBroker confirmed the most popular handgun on their platform sold was the Glock 19. It is impressive how much of a presence it has on the market, and even more so once you think about another fact.

No one questions it.

How did this company spring out of the Earth like a dandelion and, in the span of only 40 years, take it over in this manner? It’s so normal and yet at the same time, it isn’t normal at all. The Glock 17 is one of the most fundamentally revolutionary handguns in the past 40 years, changing the balance and concepts of what makes a handgun a handgun in the span of just a few years. The wondernine era ended with the Glock 17. And now, 30 years later we’re only starting to see companies catch up and one-up the concept. But it’s still impressive how it all happened. One plastics manufacturer, on a whim, elected to become a handgun maker, shook the entire tree up and won it’s position in America by a combination of a crazed shooting in Miami, a willingness to bankrupt themselves and S&W blowing their own foot off. To shine a light on it, and to finally explain to the layperson how Glock became what they did, I did what is for most gun writers one of the hardest things ever.

I chose to write an article on the Glock 17.

Because I like stupid challenges.

Video Killed The Radio Star

For our purposes now, the history begins in 1981. ’81 is a fundamental changing point of a year that gets little recognition now as the rest of that decade has been sensationalized to a point of overkill. The world has collectively fallen in love with the bleepy bloopy analog aesthetic of the mid to late 80’s in a way that has outlasted pure nostalgia, but while that age is iconic in the soft edges of VHS filtering, it’s easy to forget how it formed. The 1970’s malaise era ended in a thud, as the dueling powers of both music and culture entered a peaceful stalemate. Musically speaking, disco and rock would each hit their proverbial peaks. Arena rock did some lines, put some extra Aquanet in it’s hair and became the metal of the 80’s, while disco’s sudden crash and burn had taught people restraint was needed, and thus post-disco, Hi-NRG and dance would fill the same void. But as both genres smouldered in their ruins, one song would take the lead. The Buggles, a small band made up of singer and bassist Trevor Horn and keyboardist Geoff Downes would create an album known as “Age of Plastic”. Their hit song would take a year to come to a head, but it would be the first to sell synthesizers to the mass market. Other bands such as Kraftwerk and YMO had done so first, but Video Killed The Radio Star had some hopeful ring in it’s morose message. It didn’t stop it coming through. A new age began that day. And as the band itself would split apart and go their separate ways, so too would world politics change.

What started as an initial rift in politics within the Democratic Republic of Afghanistan would turn into a coup, and with fears that it’s new government would turn to American backed instead of Soviet, the USSR responded with an invasion. Like the Buggles, it had started in 1979 with the coup that they had done against the regime known as Operation Storm-333, placing a Soviet backed leader in charge. And in 1980, the outcry of rival Islamic nations would begin a slow and steady insurgency campaign and civil war, one that the Soviets would fight tooth and nail to enforce. More tanks would flow over the border, and the detente of 1970’s politics seemed to end alongside it. While in hindsight, many of us look at the Soviet-Afghan War as a misguided attempt by Leonid Brezhnev to maintain Soviet control over other regional powers that lead to the USSR’s downfall, no one knew that was to come in 1980 and 1981.

Both the Warsaw Pact and NATO had spent the 1970’s easing relations against each other following messy late 60’s incidents. For America and NATO, they had come out of the 1960’s carrying the baggage of the Vietnam War, and the failure of the Domino Theory giving way to the more brute Kirkpatrick Doctrine that saw many newly American backed dictatorships across Africa and Central and South America. The Warsaw Pact hadn’t fared as well either, coming out the loser of the space race with many failures and nothing to show for it, as well as internal dissent in response to the Prague Spring. When reformer Alexander Dubcek became head of the Czechoslovak People’s Republic and preached reform, the Pact preached a more hardline stance under the treads and boots of a quarter of a million Warsaw Pact soldiers, pooled from across the alliance. Excluding Romania, who said no, straining the relations between Bucharest and Moscow. As the Oil Crisis picked up, both nations elected for more peaceful relations with the signing of SALT treaties. Not to say it was quiet, proxy wars still percolated across the world, but it wasn’t open war. But now.

Things had changed, and so NATO tightened it’s boots straps and began to put more money into modernization campaigns of every form of equipment in the catalog. Electing for more moderate approaches over the complex to avoid another MBT-70/Kpz-70 program, the late 70’s and early 80’s saw the underpinnings of a myriad of efforts for modern war. New age jet fighter programs like the F-16 and Tornado would begin to see large scale adoption, as well as new MBT programs like the M1 Abrams, Challenger I and AMX-40, and even something as minute as small arms saw upgrades. As most of Europe had been reliant on 7.62 NATO rifles such as the FN FAL or the G3A3, the time had come to finally agree with the M16A1 and 5.56×45. Starting in this period, more nations would begin adopting 5.56 caliber assault rifles in favor of the old 7.62 NATO battle rifles. Projects like the FN CAL would produce the FNC, adopted by the Belgians and Swedes. Other nations would adopt foreign designs like the Dutch with the Canadian C7 rifles, and some would dust off long term projects like the British and the ill-fated L85 project. Some would even reach deeper into the catalogs, as the 80’s would begin the finalization of H&K’s long work on the G11 project for the Bundeswehr. Other nations had got onto the bandwagon earlier such as Beretta with the AR70, but the two most advanced rifles would come a little earlier. The first was the FAMAS, a long term project for the French who’s need to be finalized was highlighted with the Battle of Kolwezi, and yielded a highly modern bullpup 5.56 NATO rifle to the world. Not the first however, that honor would go to another nation.

Austria.

Alles Klar, Herr Kommisar?

The Federal Republic of Austria would be formed in 1955 with the ratification of the Austrian State Treaty, serving to coagulate the various Allied and Soviet occupied zones under one banner and create a new nation state in Europe safely. Following the war, the nation was mostly divvied up between French, British, American and Soviet occupied zones, with a tenured new government in Vienna but in an area surrounded by the Soviets. Initial tensions seemed to simmer as the nations discussed how to reunify the nation for years before coming to their conclusion. Austria would return as a new state, but one that itself proclaimed “permanent neutrality” upon it’s reunification. This new Austria was now the second alpine power to elect to forgo war mongering. That being said, that concept didn’t hold up well.

With the state of Germany at the time being split between East and West and the sight of such uncomfortable events like the Uprising in 1953 in East Germany as well as the later Hungarian Revolution in 1956 made Austria wary to fully go down the same route as Switzerland. It’s border situation was none better either. Neighboring the Czechoslovak People’s Republic, Hungarian People’s Republic, Polish People’s Republic, the German Democratic Republic in the north looming above and the perpetual wildcard of Tito’s Yugoslavia to the south, it would also elect for a more armed form of neutrality, akin to their neighbor Switzerland. They were in luck given their largest arms manufacturer, Steyr-Daimler-Puch had been reactivated prior to begin remaking cars, buses and trucks for the rebuilding Europe. It wouldn’t be too hard to rearm now, would it?

They would sign in a form of mandatory conscription, in which all Austrian males were obligated to serve nine months in the armed forces, followed by four days of active service every two years for training and inspection. The rebuilt Bundesheer would also begin pushing for new vehicle production from companies such as Saurer and Steyr for a variety of new trucks, APC’s and modified tanks that they had purchased. They’d also secure a license to produce the FN FAL within Austria as the “Stg. 58” and later on a modified version of the MG3 as the MG74. They wouldn’t simply stick to licensed FN or Rheinmetall products either, as Steyr would begin producing their own new designs as well. At first it was simply just the SSG-69, but it proved a basic framework upon which their biggest new product would come. Lightweight plastic furniture and high grade aluminum components would yield.

The Steyr AUG.

In modern times the various hyperspecific parts and features of the AUG seem quaint and simple but do remember the year it came out in. 1977. At the same time as designs like the FN FNC, there was the AUG. Full polymer furniture, progressive trigger, quick change barrel and integrated 1.5x power optic made by Swarovski. Most of these features seem quaint or outdated now, but it’s again, 1977. This thing was revolutionary, a true bean counter’s wet dream of force multiplier factors on a rifle. Not only would it become popular, it would also cause the Austrians to look into more modernization of their military structure. And while that would come in forms like more tank models and aircraft purchases, it also would include something very simple.

Handguns.

For the most part, the Bundesheer and Austria as a whole was split between three designs. None of them weren’t exactly the same, and were quite old even for the time frame. For the Bundesheer, it was split between WWII surplus Walther P38’s and M1911A1’s. Decent handguns for certain, but they were getting long in the tooth as the 70’s crawled into the modern 80’s. The Austrian Police had been early adopters of the Browning Hi-Power, putting orders of Mark I’s in the late 1950’s. More modern, albeit now it was a single action only design with double stack magazines. Three separate handguns, two approaching 40 years of age and the 1911 far older, with two different calibers and three separate pools of parts to work with.. The Austrians wanted something new and modern, and so they put out the call for a handgun trial in late 1980. As ‘81 rolled around, the timing seemed a tad more apt. The Federal Ministry of Defense would make a 17 point list of features that this new service pistol must match if it was to be considered for adoption.

It must be a semi automatic, it must be chambered in NATO standard 9×19 ammunition, it must have magazines that did not require a loading tool, it must be drop, bump, strike and shock safe from accidental discharge. It must also survive a 15,000 round endurance trial as well as surviving firing a deliberate 5,000 Psi overpressured round. The requirements were sent out to a wide variety of companies, and models slowly began to trickle in. H&K would send three guns, the single stack magged P7M8 and it’s double stack brother the P7M13 alongside the P9S. Beretta would send their product improved 92SB-F model, the precursor to the 92F that would later become the M9. SIG-Sauer would send the P220 and P226, the handguns already becoming popular with adoptions in Switzerland, Japan and the P6’s adoption by the Bundespolizei in Germany. There was also FN introducing an improved Hi-Power, probably the Mark III model. Then there was the domestic manufacturer of Steyr. Their handgun, the GB was a wildcat of a handgun. Originally designed in 1968, the handgun was a mixture of kooky ideas. Gas delayed blowback, firing from a double stack, double feed magazine with a top ejection port, polygonal rifled barrel and so on. It had initially been pushed by Steyr in 1971, negotiating the sale of both it and the MPi-69 SMG to the Bundesheer. The deal however fell through and both pistol and SMG weren’t adopted, but Steyr simply shrugged, improved the design and bide their time for another chance.

They almost had it until there was another bit of news. There was another Austrian handgun in the trial.

Who?

No One Makes Polymer Like Gaston

Gaston Glock

Is a VERY strange man.

And I say that as a compliment, not an insult.

Born in 1929, Gaston would take an interest in the burgeoning market of polymer products in the wake of WWII. Initially starting in his backroom shop in the town of Deutsch-Wagram, he would focus on consumer products first. The quoted joke of “The Glock 1 was a curtain rod and the Glock 2 being shower curtain rings’ ‘ isn’t wrong. While this limited work did bring in money, it didn’t provide much room for expansion. But when Glock got a contract to manufacture plastic components for the new Bundesheer combat knives, now known as the Glock P76 “Feldmesser”, that would get the ball rolling. He’d begin work with injection molded plastic and slow expansion of his company. And critically, it gave him a contact in the Federal Ministry of Defense. So when the requirements for the pistol trial were drawn up, he got them. In a normal man’s mind, he would shrug and go back to working on knives and entrenching tools. But Gaston liked challenging himself. So he elected to make his own pistol. From scratch.

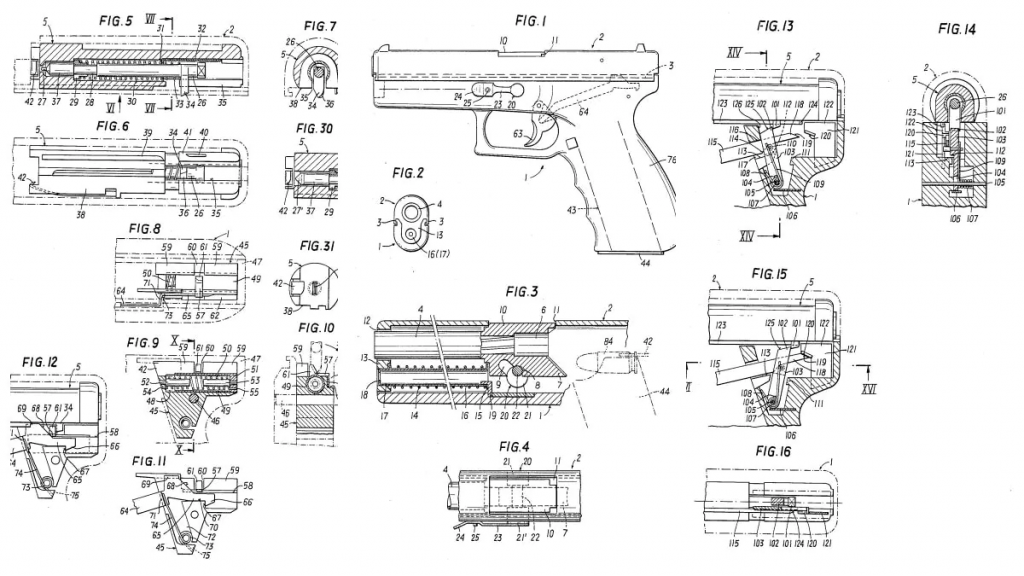

The concept of this being as wild as you’d expect would require outside help, so as Gaston would expand his company, he’d bring in a mixture of various outside help for the design of the Glock pistol. Military, police and civilian shooters, as well as engineers to help him iron out the design. And that design would pool it’s influences from various Austrian sources. The striker system borrowed from the Roth-Steyr 1907, the lockwork being a modified Browning camlock system, and with a number of new features such as a trigger blade safety, polymer frame and polymer mags. While they weren’t the first to do things like a polymer frame, Alex Seidel’s weird project gun that was the VP70 had beaten them, they were the first to coalesce all these ideas into one pistol. And with a man like Gaston at the helm, who would shoot his prototypes left handed so that, if it blew up and destroyed his hand, he could still write with his remaining hand, they were in good hands. Incredibly dedicated and mildly insane hands, but hands nonetheless. In April of 1981, he’d submit the first patent documents for his new handgun, and given it was his 17th patent, it would earn the name of “Glock 17”.

The fact it had matched both the amount of requirements for the trial as well as it’s magazine capacity is serendipity.

Entering the trials in ‘82, the Glock 17 would be up against a large wall of opposition, and worryingly it was winning. And even wilder, at the end of 1982, both the Bundesheer and Austrian Police accepted it as standard. The handgun would be adopted as the Pistole 80 by both forces, with an initial order of 25,000 for both. A random polymer manufacturer who experimented with handgun design had not only won the trial, but had beaten several much more well established designs in the process. This result shook the gun world to its core, and even worse was how it would continue to get more popular. The Glock would miss the ability to be submitted to the XM9 trials, as the DoD requirements would mean retooling and missing out on production quotas for the Austrian orders, but later Swedish-Norwegian joint trials from 1983 to 1985 would yield two more adoptions. The Norwegians replaced their 1920’s vintage Konigsberg M1914’s with their own Glock, dubbed the Pistole 80 like the Austrians. The Swedes would bide some more time, replacing their even older 1900’s vintage M1907 Brownings with their new “Pistole 88”. Both nations would subsequently see their police forces buy Glock handguns later on. With these, the Glock 17 would become a standard NATO classified sidearm, and slowly eke more and more police and military sales as the 80’s continued. But the passed on XM9 trials lurked in the back of Glock’s mind. How would he worm his way into one of the largest and most popular handgun markets of the world? And even worse, get the police sales that would print him more money than anything else?

Turns out it’d come from an unlikely place.

Miami Heat

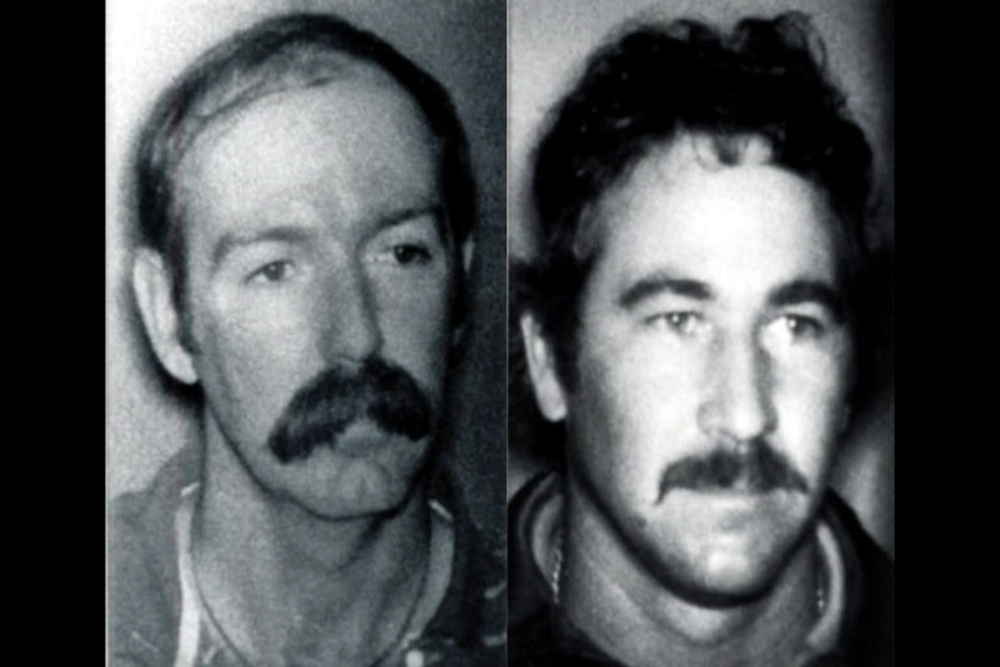

In early 1986, the FBI were trailing the case of two prolific bank robbers in Miami-Dade County, Florida. The men were Michael Lee Platt and William Russell Matix, two former US Army soldiers who would turn to an interesting life following the dishonorable discharge of Platt in ‘79. Both would reconnect in southern Florida, be implicated in the murder of each other’s ex wives but get away as the cases turned against them. They’d found a tree care service, remarry and begin a life of crime in 1984, murdering Emilio Briel and stealing his car. From there, they’d begin a series of robberies on armored cars in the Miami-Dade area, racking up a very slim but noticeable body count.

The FBI would put them under surveillance and began tailing them when they killed a separate man, Jose Collazo after the pair killed him to take the man’s ‘79 Monte Carlo and then robbed a proper bank branch. A rolling stakeout of the area would lead to a confrontation between the pair and an FBI surveillance team of eight agents. These agents would trail the Monte Carlo, attempting to make a traffic stop that ended in the robber pair crashing their car. The men would get out and engage the trailing FBI team with a Mini-14 and a few revolvers, and in a five minute gunfight both groups would expend 145 rounds each at each other. The gunfight that ensued ended in both suspects killed, but two agents killed and five wounded, three seriously. This event would become known as the 1986 FBI Miami Shootout and herald several changes to the FBI.

The shootout itself is a mess of details, conflicting reports and collar pulling conclusions made by the FBI and Justice Department. If you want a full overview, I would suggest watching Paul Harrell’s video on the subject matter. So apologies if you wanted something more in-depth, but we must stick to generalizations. In the wake of the shooting, the FBI elected to blame the lack of “stopping power” of the agents at the time, over other issues. The FBI had been forward in the adoption of a new semi-automatic handgun, the S&W 459 which was adopted in 1983. However, most agents involved in the shooting were using .357 or .38 caliber revolvers, the former FBI standard issue S&W Model 13’s and Model 19’s. Outgunned by two demented tree cutters with Mini-14’s, the FBI chose to pursue a path of mass firepower over improving agent accuracy, and this path would lead down a myriad of S&W handguns in calibers such as 10mm Auto and the creation of the .40 S&W. It did however highlight the critical issue of revolvers in police work.

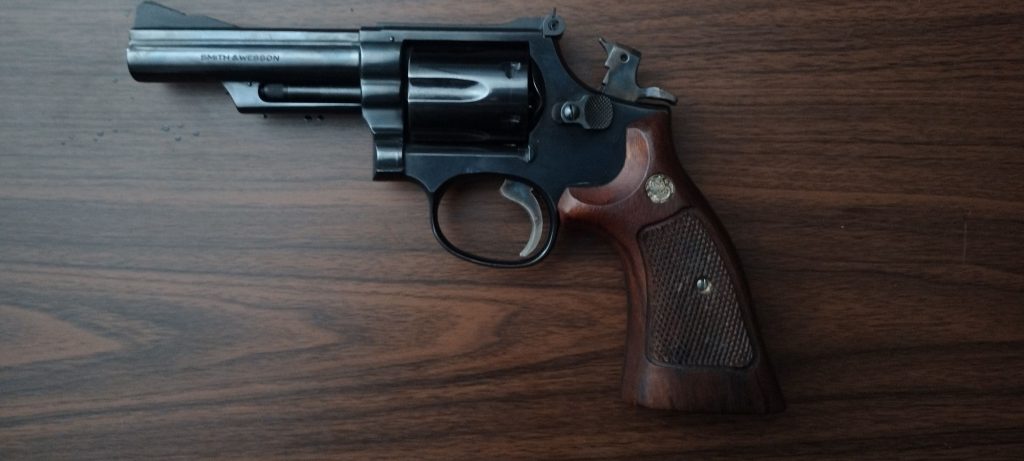

While semi-automatics had been in common circulation for decades prior to 1986, the police agencies of America had elected to maintain the tradition of revolvers. The 1950’s and 60’s saw the rise of .357’s in use like the aforementioned Model 13 and Model 19, but for PR reasons as well as the rough recoil, many were issued with simple .38 +P ammo. While speedloaders and training officers in effective double action fire helped bridge the gap, it still wasn’t a real solution to the root problem. Semi automatics had been adopted in limited numbers as far back as the S&W 39 in 1967 by the Illinois State Police. However many agencies didn’t want to take the plunge due to a fundamental issue in the difference between the new and old. While you can point at it being an issue of not wanting to change with the times, there’s also a deeper issue that was steeped within the training regimens of these police agencies at the time. And that was the fundamental difference in what double action meant.

Allow me to use a visual metaphor.

Revolver Double Action Versus Semi-Automatic Double Action.

To explain the dilemma of the modern American police department around this time, I have decided to use a few visual metaphors here. To represent the classic American wheelgun that had become popular with the police agencies at around the 1950’s and 1960’s, a S&W Model 19. 4 inch barrel, target sights, thick S&W Rosewood grips and a .357 chambering so you can fill it with those aforementioned .38 +P’s. To represent the new and rising wondernine 9×19 handgun, we have a Beretta 92FS. In this case, it is a modern M9A1, but it’s still mechanically the same gun. 9×19 caliber, single action/double action and mag fed. Both guns in basic terms are the same, they are both single action and double action.

The fundamental difference however is in the single action and double action. With the Model 19, and any other normal swing out cylinder revolver, the hammer must…

Be cocked for single action. And so on for every shot. As a result, the handgun is carried and fired primarily in double action. So much so that departments trained their officers in effective and accurate double action fire with revolvers such as S&W K-Frames. However.

New wondernine handguns like the 92 series have a different mechanism, primarily due to their action. Semi automatics tend to be carried and have their first shot fired in double action, especially with models that feature a decocker like the P220/226 or the 92’s safety. But once the action has fired that double action shot.

The slide cycles back, ejects it’s spent case, loads a new one and also cocks the hammer. Thus meaning every shot afterwards is in single action. And this difference, as basic as it sounds, is the reason many police departments were hesitant to switch over even after the Miami-Dade shooting. The training programs that they had constructed around accurate double action fire were mainstays for decades, to an extent that the concept of “precision pistol competition” was started by police officers to train around that fact, the grandfather of practical shooting courses. While agencies would pick up interest in semi-autos over time, there was one gun that skipped past this hurdle.

The double-action Glock 17.

Stashin’ The Glock An’ I Thought You Knew It

In 1985, Glock would set up an American holding company in Smyrna, Georgia, where Glock USA resides today. Glock would get ATF approval for importation in early 1986, ironically not too long after the messy Miami shootout. If the irony wasn’t enough, the gun’s first appearance to the American public would be in an episode of Miami Vice, “Cuba Libre” as the sidearm for a group of foreign backed Cuban revolutionaries. The cutting edge Glock fit the role perfectly, showing how there was more than meets the eye. It would also begin cropping up in movies at the time, and rather infamously in Die Hard 2. The “Glock 7, a porcelain made gun constructed in Germany” would make normal people spooked, and anyone who knew better laugh. That, however, wasn’t solely just writer panache. It was an echo of legitimate gun control discussions at the time.

Glock was entering the American market at the same time the modern gun control debate was picking up steam, buoyed by the political success of the 1986 Hughes Amendment and aiming to solve crime by outright banning ownership of firearms. It’s true that, over 50 years, legal machineguns were only used in two crimes, both of which by law enforcement officials. But it was the 1980’s, and the supposed success of the early stages of the drug war had politicians gliding on any issue being solved with a ban and some enforcement. And the Glock 17 was just the hot ticket item. It’s new polymer frame spooked establishment politicians, and articles began to be published calling it a handgun “tailor made for terrorists” and able to be snuck through X-Ray machines at airports.

Various members of the US Senate would try to create gun bans on “plastic guns’ citing the concept that these handguns would be able to be snuck in illegally through X-Ray machines in airports. The concept is wild, and inaccurate as around 85% of a Glock is made of metal, including internal components but that didn’t stop a gun control happy lobby that had “success” with the 1986 Hughes Amendment. House Majority Leader Thomas Foley and Republican senator James McClure would draw up two competing documents known as the “Firearms Detection Act of 1988” and amending the FOPA Act of 1986. The men would reach a compromise with the Undetectable Firearms Act of 1988, backed by none other than the same William Hughes behind the Hughes Amendment. It placed a minimum amount of steel in a handgun to be allowed for importation, as well as some unconditional power to the Secretary of the Treasury that gave them the ability to ban any firearm. That latter part would be revoked and, upon further inspection, they found that no pistol actually violated this weight limit. Including Glocks.

History never changes. Many involved in the process would later go on to write up the 1994 AWB and work with “Handgun Control Inc”, which you’d know by it’s post 2001 name of the “Brady Campaign.”

Regardless of the legality of the Glock 17, the media panic around “plastic guns” gave the new company an uphill battle in regards to getting their products accepted by the wider market. Glock was walking into an area dominated by the rising wonder nines like the new Beretta 92F and FS, recently adopted as the M9, the SIG P226 and the S&W 4/5/659 series. It was crowded. So, rather than simply compete, they’d go directly to that new burgeoning market share of departments who wanted to replace revolvers with something that made sense. Glock would begin opening up negotiations with departments, with incredibly generous terms if they were willing to experiment with the new handguns. Some were offered the VERY lofty term of Glock willingly buying out their older stock of handguns and replacing them with new Glocks for almost free. A move that more than likely cost Glock a bit in the beginning, but would become instrumental in the increased rise of Glocks popularity with the police.

From 1987 through to 1991, agencies would begin slowly shifting to the Glock 17 and recently introduced Glock 19. Even the holdout area of NYC, which had actually banned the ownership of Glocks, didn’t hold up much longer. Stephen D’Andrilli, a former NYPD officer turned gun rights activist was assisting a variety of NYC citizens to legally purchase handguns, and took annoyance when the NYPD denied one for a Glock 17. Going for the jugular, he’d apply for a freedom of information request, exposing that the Police Commissioner of the entire NYPD, Benjamin Ward, had been allowed to carry a Glock 17. By the next day, the NYPD lifted that ban. They claim to have been in the works of revoking it that same week, but I firmly doubt it. Still, by this stage, Glocks were becoming VERY popular on the American market, both for civilians and police. And not everyone took that well. Especially one company who was regularly the one being replaced by Glocks. Smith and Wesson.

The Sigma

It is hard to explain how deep in the police pit S&W had dug themselves into by the late 1980’s and early 1990’s. Nowadays we are somewhat used to how it has become a brand of sorts, stamped onto extra products beyond S&W handguns and rifles like watches, knives and stickers but that pales in comparison to how deep it was. At this time period, S&W had gone deep into the police products market. Unlike competition like Colt, Remington or Ruger, S&W was established first and foremost on revolvers, ones used by police agencies and so they elected to become a one-stop shop for departments in need of equipment. And that was backed up far before Glock had entered the scene.

In the late 1970’s, Big Blue would be purchased by a holding company known as Bangor Punta, a Fortune 500 company made by the merging of the Bangor and Aroostock Railroad with the Punta Alegre Sugar and Railroad of Cuba, and would be lumped together with a variety of other companies ranging from Piper Aircraft to Brazilian gun company Forjas Taurus. This put S&W next to a variety of other companies that could provide them with a new arsenal of products to sell to their customers, and ones who were repeat customers as well. So they’d develop a new line of products with this capital, based around that. Starting in the mid 1970’s, S&W’s lineup would fill a large net of niches for a modern police department, pooling every connection they had with Bangor Punta.

For a department at the time, S&W provided duty revolvers, snub nosed revolvers, shotguns taken from companies like Noble Manufacturing and Howa, police batons, holsters, gun belts, connections with early speed loaders as well as tear gas grenades and launchers courtesy of Federal Chemical Works, another company in the Punta umbrella. They had become the 7/11 for police brutality, and they’d continue that trend into the 1980’s as well, expanding the popular S&W 39 and 59 into the 4/5/6 series. Alloy frame, steel frame and stainless steel, and now with compact models inspired by the ASP and Devel conversions guns. Everything was working, it was printing them money, it was going great.

Until Glock.

Most agencies at the time were de-vesting in their earlier adopted revolvers in favor of Glock products, and showed less and less interest in S&W’s offerings. And this would lead S&W into finding any way of competing. And even worse, Punta had been bought out and S&W was sold off to another holding company, British based Tomkins PLC. This meant that their source of big income was now cut off, and while they still had somewhat of the means to maintain it, they needed new products and fast. And so they adapted. tory goes that the acting CEO of S&W at the time, Steve Melvin, would hold a meeting with the R&D department of S&W, discussing a new striker fired handgun. When the engineers shot back a rebuttal saying they couldn’t really make a similar handgun, Melvin would pull a Glock 17 from his jacket, set it on the table and say “if you can’t make a better gun than the ‘motherfuckers’, then copy them!” The engineers took it literally.

In 1993, S&W would release the new Sigma model, coinciding with their new line of stainless steel revolvers and semi-autos. The handgun was a polymer framed, striker fired double action only design in a wide myriad of sizes in 9×19, .40 S&W, a compact model in .380 ACP and a rare version later on in .357 SIG. The handgun was and still is a flagrant clone of the Glock series, so close that certain parts are interchangeable between the two. And it would be sued immediately by Glock in 1994, citing “tortious acts, including without limitations, patent infringement, federal unfair competition, common unfair competition and deceptive trade practices.” The court battle would drag for three more years, before an out-of-court settlement would be reached with a design change and an undisclosed payment made to Glock. The Sigma’s reputation tarnished, it would become more and more irrelevant before the plug was pulled in 1999 in favor of a partnership deal with Walther to make a version of the Walther P99 for S&W. That, combo’d with the new CEO Schultz pandering for pro-gun control measures like smart guns in the late 90’s, would tarnish Big Blue’s reputation even more. The final nail in this coffin isn’t the Hillary Hole fiasco, but the big loss.

The FBI would replace the S&W 459 with the S&W 1076, a 10mm Auto full house semi-automatic that would then quickly be pulled out of service for the high recoil and muzzle blast of 10mm as well as QC issues with the handguns such as broken safeties and brittle grip assemblies. The FBI would cancel their order of 1076’s and order a new semi auto from S&W. This would lead to a new “10mm Lite” loading that S&W would work on and dub “.40 S&W.” The intention was that S&W would provide a new version of the 1076 handgun that would be chambered in .40 S&W to replace the portable hand cannon for the FBI. This would be the S&W 4006, introduced alongside the new cartridge. However before they’d even hit the market, there was a gun already in .40 S&W. It was…

The Glock 22 and Glock 23.

Because of the development of the 10mm Auto Glock 20, Glock had already developed their own .40 S&W version of their standard handgun before S&W did.

And to add salt to the wound, in 1997 when the FBI adopted a new sidearm, they chose the Glock 22 and 23. S&W would never see adoption by the FBI ever again.

The Glock 17

So, finally we get to the end product. A Glock 17. More specifically, a Glock 17 Gen 5. This is the newest version of all Glocks, introduced a few years back to retire the questionably “better” Gen 4. It has a small host of features such as a new “Glock Marksman” barrel, flared mag well, ambidextrous slide releases, customizable back straps, no finger grooves and every single conceivable edge sanded off to make it more round. All of these are actually good things, good on you Glock you reinvented the wheel and gave me a race gun version of a Gen 1.

This is a semi-automatic handgun firing 9×19, it uses a modified Browning cam-lock system for it’s action. It has a 4.49~ inch barrel so do as men do and round it to 4.5, and it weighs 1.38~ pounds unloaded. It fires from Glock pattern magazines, which are also 17 rounders. And are some of the most ridiculously common magazines in America. You sneeze near a gunshop and someone hands you a GL9 to wipe your nose with.

Glocks in-general have a weirdly ambivalent feeling in the hand. Solid for sure, but still strangely light especially without a mag inserted. A lot of the major weight of the gun seems to be stuck in that magazine, and while that’s a handgun issue in-general, it’s noticeable on the Glock 17. Mind you, this is being written by a man who’s first handgun was that M9A1 from earlier. My brain is not used to handguns not weighing as much as laptops.

The grip is mildly textured with the standard Glock vague-stipples and in a way that invites any wannabe home gunsmith to begin making his own with a small drill bit and enough time. I personally like and dislike the stock Glock stippling. It’s good enough to grip the gun but it doesn’t hold on really well once my hands get sweaty for whatever reason. Goon tape or whatever method you do to scrub off the calluses of your hand is a good choice. Also since this is a Gen 5, we have removable backstraps. Or one. Mine was used, I only have one. And all I’ve done beyond that is slapped a TLR-1 HL on it. Because it’s the min-max of all weapon lights.

At the sides, plural since it’s a Gen 5, we have the three major controls of the Glock 17, and by proxy every Glock ever unless you’re cool and have a Glock 18. Or the funny ATF bait Wish switches. Which I don’t have because I like my dogs alive, unshot and my house not burned down. We have the trigger, magazine release and slide release. The mag release, in this case enlarged, is big, easy to hit and nice and simple. Nothing weird or convoluted, just smash your thumb into the button and release the mag. Gives me a chance to mention the mags, the Glock 17 mag is great. Solid polymer body with steel feed lips. If you somehow manage to make one of these NOT work, you are doing something horrifically wrong. If the capacity isn’t high enough, you can augment this with anything from extended floor plates to weird mags like the Magpul GL9’s. Those work, in theory.

The slide release is this tiny little chunk of bent over sheet metal, one on both sides since we are the fancy Gen 5. It’s simple, effective, falls right under my thumb and is easy to operate. Not much to talk about there. Then the trigger. Which means I have to talk about the striker. And the “safety”. Right there’s a bit to break down. The Glock’s trigger and trigger blade are the thing that weirds out most newguns who pick these up, primarily because of the classic “it doesn’t have a safe-tee!” which is the sole reason in this world the M&P sells.

The Glock safety is a trigger blade that blocks the trigger from falling or activating unless depressed. That is your safety. You are also a safety. Remember Cooper’s first rule. Glock triggers operate as a weird two-stage trigger given the half-cocked striker system that it uses. Pulling the trigger back rebounds the striker until you hit the “wall” that then drops it. It’s a weird mildly lurch-y feeling, but once you get used to it, it’s slick. Fittingly, reminds me of staging double action revolver trigger pulls. It works. And it works repeatedly which makes it fun. A Glock trigger is the same every single time, mag after mag.

Sights, in this case, are the Glock brand night sights. Three big ol’ tritium dots. Not super bright, but they remain pretty decently visible for a long time without the constant need to shine a light in it to recharge the tritium, which is nice. Standard Glock’s come with the Patridge sight, as seen with the Glock 19 next to the 17. Most people scoff at it, but I find it’s a decent close range quick-shooting sight, and it’s also REALLY easy to swap should you want to. Beyond that, there’s not really much to talk about given the Glock’s pretty sparse feature set. The slide is smooth, mildly less boxy with the Gen 5 with a set of wide, grippy slide serrations in the back. The front of the gun is rounded and leads you to the accessory rail.

For the purpose that I have this Glock for, I stuffed a TLR-1 HL on it to blind people. The Glock accessory rail is one of these weird pseudo-proprietary things that was the sales pitch for the Gen 3’s back in 1998, in the same way they sales pitched you Smash Mouth. Like the various other 90’s guns with similar rails, it’s a special little thing that sorta interfaces with 1913 Picatinny. IN THEORY. In practice it’s just a little wider and so everything jiggles a bit. I know this is primarily my fault, the Streamlight bag came with a “GL” adapter and I didn’t put it in, but still. That being said, it’s a front rail on a handgun. You’re slapping a light or laser/light if you’re feeling daring on it and calling it a day. If you’re trying to zero the laser on this to point of aim so you can rely on that, you are a level of stupid that will require significant medical study for the betterment of humanity.

How does it shoot? It’s a Glock.

It shoots fine.

The critical issue that hits most people like myself when discussing a Glock is the ennui that is shooting and using a Glock. A Glock, regardless of caliber, version or size, works. It shoots the bullet. The trigger cocks the striker fully, then with the final bit of travel drops and fires the gun. It works in a way that defies any attempt to explain it. It is a good gun that shoots the bullet.

Which is why I wrote this article. This is 100% a challenge to myself. Talk about the gun that no one talks about. A gun so boring we all write it off and don’t think about it.

One of the biggest problems for a person with no firearms experience is understanding the Glock. Because no one really talks about it in a way that makes sense. They shrug and say ‘it’s a good gun’ but they don’t give a reason why. The reason people buy worse Glock clones over actual Glocks is because of a lot of reasons, but this fundamental one. No one knows why a Glock is good, so it doesn’t get trusted. They’ll buy anything else that has a semblance of more trust in it. The M&P with it’s safety, the P320 with it’s “military adoption”, or the XD for the ironic “well it’s made in America” thought process. They’ll dodge the point that the Glock 17 brings to the table.

A Glock 17 is a better gun for a new shooter to buy than any other because it is a basic handgun. It works out of the box, through whatever silly ammo you feed it when the budget gets tight. It will shoot steel, it will shoot brass, it can probably shoot polymer cased ammo. It shoots FMJ, JHP, HP, and the 19 versions of meme hype ammo. It will shoot in the desert, jungle, tundra, city or even underwater. It can be modded to the nine hells and still works like you didn’t change a thing on it. When you are building up a skill, regardless of what it is, you need to iron out the fundamentals. Handgun shooting is a large amount of fundamentals that stack on top of each other, building up until you’re good. I say this as a man who is trash with pistols and is relearning how to shoot them properly. You will shoot many thousands of rounds of 9mm to get decent, and more to go further. Repetition in shots, hand placement, grip and so on. And no gun will do that better than a Glock. Because nothing on it breaks, everything on it works, you don’t have to work around weird features beyond a creaky two-stage striker fired trigger.

The Glock 17 is not a great gun. And it doesn’t have to be. It just needs to work. And that fact is how one company swept into the world markets and has become a standard for all modern handguns. And why you should put down the Springfield XD the counter monkey is talking you into, pick up a Glock 17 or 19 and keep hammering away at targets until you get good. Because it will happen. And you can do it. And the amount of money you’d spend on a marginally more effective first pistol can be spent on ammo, targets and training. Skip the fancy shit, go boring and run that boring piece into the ground. And when it fails, you’ll have enough money for another one.

Don’t feel bad for sucking at first.

We all gotta start somewhere.

No P320?

I actually thought of a Beretta 92